An Enthusiast’s Guide to Heraldry

Or

An Essay On The Science of Armory and the Sociological Necessity Thereof

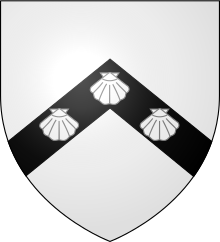

The Arms of Sir John Hawkwood (c. 1323 - 1394) Argent, on a chevron sable three escallops of the field

By “Felipé Naranza” Casilló y Réal,

Or CyR

Published by the University of the East Pacific

December 2021

This work is distributed under a https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

As a student of culture, history, anthropology, military science, and simply in general, good stories, I find myself drawn to the period of time known as ‘the Dark Ages,’ Medieval Europe, in no small part due to the influences of friends whom are authors and historians, thanks to the interesting counterpoints between the modern romanticisation of this period and the actualities of life and society that people faced. Alone in this mindset I am not, and so I endeavor in writing this academic piece to bring some of the accumulated references and knowledge I have acquired to the community of Nationstates, and The East Pacific.

One such historian friend recommended that I delve into the game this region is part of as an exercise in creative thinking and writing; a way to deposit my own fictional creations of nation and people into a living medium. I have not been disappointed, and so I hope to repay some small amount of the welcome extended by the residents of this region. My appreciation for the community may hopefully in due course be reflected in the appreciation of the community for this Enthusiast’s Guide to Heraldry.

The practice of heraldry has existed in a codified form for hundreds of years. It is a prominent and easily recognizable part of history, fantasy, and genealogy. Knights wearing shields covered in colorful designs are what first comes to mind for many. This impression is only superficial; heraldry encompasses more than just telling which side is which in a joust. Likewise the definition of heraldry as related to coats of arms is superficial, the correct scientific and artistic term is ‘armory.’

Although feudal heraldry is best documented and developed in Europe, north Africa, and west Asia, it is arguable that the concept heraldry represents is as old as human history. Ever since two groups of different people have existed, it has been necessary to differentiate them in some form. From the societies of both the New World and the Old, examples of art and design to define the individual, family, or group have always been present.

This writing is, in the end, for the benefit of the reader, and while a comprehensive analysis and history of human expression for delineating purposes would be equally as academic, I’m sure most of those who are interested in heraldry are interested in what can be termed the ‘classical’ sense. The design and usage of those devices of arms for banner and shield as became the practice in post-Roman Europe, up to today. We will be referencing largely English but some German, French, and Spanish sources on the matter, mostly in proportion to the surviving records, practices, and examples of heraldic tradition in those societies. I owe a large portion of the research to Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, whose passion for the art and science of arms is reflected in his many published works, not the least of which are The Art of Heraldry: An Encyclopædia of Armory, and The Complete Guide to Heraldry, of which I have consulted a great deal.

The contents of this writing will therefore be: a history and explanation of heraldry and its related practices, an exploration of the functionality of heraldry in classical and modern societies, a comprehensive but no means totally exhaustive explanation of the terms and regulations used to describe and design arms, and finally a description of the most common parts of arms one may encounter within the context of European heraldry. I will finalize my writing with a glossary of sources consulted so interested readers may explore on their own academic adventures. So published in six contained but complimentary parts, the contents therein will be hopefully of much use and reference to those citizens of The East Pacific.

History

The term ‘heraldry’ is, to what I am sure is the confusion of some readers, not explicitly referring to the concepts and practices surrounding coats of arms and such devices. Rather, heraldry originated from the usage of heralds to administrate the aforementioned subjects. Thus, while ‘heraldry’ may be what a modern interested party may think of and indeed discuss with other parties to no miscommunication, those who study and partake of such traditions use the term ‘armory.’ Armory, specifically, refers to the science of, and the rules, laws, regulations, and traditions that govern, the use, display, knowledge, and meaning of those particular pictured signs appearing on shield, helmet, or banner, with the intention of describing the bearer of such as distinct and separate from any other individual that bears shield, helmet, or banner.

Hereafter, in order to delineate between the functions of each, I will refer to the practices that fall under the purview of an appointed officer as ‘heraldry,’ and the practices that involve the design and display of devices as ‘armory.’

The origins of armory cannot be definitively traced. Indeed in many texts and many cultures it is taken for granted that certain groups have been represented by certain images. Indeed, long before the cross was associated with Christianity, one of the most basic decorative devices was a line intersected at a right angle by another line. The use of animals, designs, and colors to differentiate tribes and people can, however, be seen in a definitive manner in many ancient civilizations. Babylon was tied to the lion, the Athenians the owl, the Egyptians the Ankh.

Egyptians as mentioned places great importance on the Ankh. This symbol was used in hieroglyphics to represent the word ‘life,’ and as communication and concepts evolve, was eventually taken to represent the concept of life itself, and so found itself in artistic representations of gods, of general decoration in temples, and in the finery and accoutrements of priests and pharaohs. This allowed individuals occupying every strata of society to be aware that those who bore the Ankh and the gods were inextricably linked, whether the observer be literate or not.

The Ankh, while a demonstrable example of a way to separate certain kinds of people through symbolism, is not as close to the core concept of armory as that of Hellenistic Greek city-states and their own symbology. Each state was represented in figurative speech, in lore and myth, and in everyday life by a particular aspect, especially during times of great strife and conflict. Athenians used the owl as their figure and representation, being a city so close to Athena as to take her familiar as their standard. In much the same way the Thebans used the Sphinx, the great monster so overcome by the mythological king Oedipus. While some experts do not consider these Greek symbols, though included on military fixtures including shields, to be armory, it bears including within this history so as to demonstrate how the practice and mindsets behind it develop.

Of much kinship to that of the Greeks, though an example I am sure is much more commonly understood, is that of the Roman Republic and Roman Empire. The standards used by Roman military forces are of some renown, most prominently the Aquila, the eagle. Predating the Aquila is a much more humble significant, the manipulus. Termed such was a handful of stray, hay, or ferns atop a pole, and is thus what history describes as the earliest Roman military standard, being carried by units known as maniples. Succeeding these were metal honorific figures of the eagle, the wolf, the ox, the boar, and the horse. Military reforms in 104 BC by consul Gaius Marius saw only the eagle remain as a significant during the reorganization of maniples into the widely-recognized cohortes.

The Aquila became the symbol of representation for the Roman Legions, each Legion having their own unique design. The cohortes for their part had fabric-woven standards resembling snakes named dracones which each again were specific to unit. This is an early and well-known form of armory as it is recognizable today; each Legion carried the Aquila on top of a pole upon which was also other statuettes or fixtures, and a small standard with the Legion’s numeration embroidered.

This full representation of the Legion was linked to the unit’s identity; the eagle was the most noble and powerful representation in Roman society of Jupiter, their chief god, and for the Aquila to be lost or captured was an offense of the highest order. Such was the importance of this symbology to Roman social consciousness that the eagle continued to be used in those states that thought themselves successors to the Empire, namely the Byzantine and Holy Roman Empires, and further influenced the general popularity of such a charge within armory.

In what is hoped is a forgivable advancement closer to the present day, we may start to examine the origins of proper armory as is understood in contemporary contexts. Post-Rome, European feudalism took a more rigid shape as society evolved past the tribe system. Feudalism is defined as a system wherein people who worked the land would be subordinate to one whom owned the land and supply them resources in exchange for military protection, and this landowner would in turn provide fealty and military service to a higher landowner in return for owning the land, so on and so forth. This societal system can be applied to many periods and places across the globe, but most generally, and for the purposes of this academic exercise, feudalism is specifically focused on Europe, between the eighth and sixteenth centuries at maximum.

In this admittedly limited view of geopolitics and sociological structure, which omits for brevity the technicalities of governance and everyday life and does not wholly describe nor demonstrate the evolution of civilization, there arose a need for differentiating peoples under different landowners. The most basic requirement of feudalism is that an individual provides service to another individual in a higher social strata in exchange for legal rights. By necessity of the rather tumultuous nature of the political climes this service was of the majority, military in nature. Therefore, it would be an accepted part of life for large groups of armed persons to travel to foreign lands - sometimes as foreign as the next valley over - in order to visit harm upon whatever inhabitants or structures they would encounter.

This mechanism for acquiring wealth and settling disputes has one large issue upon which armory came into existence: how do you differentiate between one large group of armed persons from another within the melée of close combat? In a more structured sense, the issue becomes one of battle order and personal organization. While an army may be fighting a campaign against a foe that does not speak their language, thus enabling at least a basic auditory means of identifying whom to stick a spear into, lack of unit delineation and a way to tell which troops were which landowners would limit tactical deployment quite annoyingly. As the population increased and more levies were able to be conscripted, larger and larger armies could form, exacerbating this dilemma.

Thus began to develop the science of armory, whereupon a landowner would choose a symbol or colour or combination of such designs that he would have a device of his own, (hopefully) unique and able to be displayed on shields and banners to inform the feudalist military world that this block of spear-carrying illiterates served this person. This was a key component of armory that can be discounted at first glance. Landowners chose to use designs and symbols rather than any numerals or linguistic characters because, unlike the citizen soldiers of Rome, most feudalistic armies were conscripted masses of farmers and craftspeople and other such persons who occupied social rungs that made reading a rarity amongst them.

The passage of time goes hand in hand with the progress, however glacial or roughshod, of civilization, and in the realm of armory this was ever the case. Borders changed, languages developed, cultures began to coalesce, and there became a certain national identity for people living in certain lands of Europe. The idea of having arms (thus here described as a device that is displayed upon a shield, helmet, or banner, though can further be displayed on certainly any material one wishes) was a more simple association between the concepts of owning land and liege lords requiring military service of those who own land. It was necessary to define what troops were whose in battle, and thus the landowners employed arms that became associated with the families and lands it was used by.

Indeed a point to be touched upon later is that locations and people have distinct sets of arms; even while a family may indeed inhabit and own a particular set of lands for generations, the lands themselves and the title that gives ownership of them can often be found as possessing distinct arms from that of the family.

As the practice of armory became ingrained into medieval society through military necessity, the memetic properties of information evolved the meaning of armory in the consciousness of the people. Such was the link between devices of arms and military service that eventually the parlance of ‘to take up arms’ or ‘to bear arms’ became synonymous with martial activity. Further, however, is the eventual though natural link between status and armory.

For one to own land, one must provide military service. For one to provide military service, one must ensure one’s troops are separate and distinct for ease of tactical and strategic means. For one to ensure troops are distinct, one must have arms. Thus, the possession of arms became an expression of importance, for if one owned land, one was important, for this places the landowner in a position of authority over other persons.

The usage of arms within conflict also brought a more prestigious aspect to their bearing. Great wars and crusades across the continent would see large clashes of troops, desperate and long-fought sieges, and vicious raids into undefended countryside. The deeds and daring of those at the forefront were due to these persons of great skill and renown benefited from training and education not normally available to any individual on account of wealthier upbringings. As the noble members of European society made names for themselves so too did they make reputations for their arms.

This preoccupation with the social matters of armory further ensured that science would develop as a respected and eventually codified matter that was nearly as important as who owned land. Arms became an honor to be bestowed or earned, indeed even on occasion stolen. As arms were known at this point as a display of honor, and so many groups and individuals and families and lands and titles were represented by increasingly complex arms, the office of the herald was conceived.

Heralds are more than a simple position of wearing a tabard and announcing the arrival of a person of import. The sovereigns of Europe often assumed themselves the total control and dispersion of arms and were, by at least 1390, responsible for the ultimate matters upon the arms of those in their purview.

In the realm of England, for examples sake, there existed the offices of the King of Arms. This position was one of utmost importance to armory and heraldry, an evolution from that military office of Earl Marshal. The Earl Marshal being the highest appointed military rank in the Kingdom of England, he was responsible for the array and deportment and general organization of the various bands and units that made up the assembled armies of the English lords. Naturally, according to what has been discussed here, this involved a great many ensigns and flags and ordinaries and banners according to each lords own arms, and to remember and catalog each of these was no small feat.

Therefore, the Earl Marshal would deputise to him officers such that would concern themselves solely with the military knowledge of the arms of England, to assist the Earl Marshal with his duties. These officers possessed such information about the arms of their nations lords and the lords of enemies and foreign lands that they were often afforded military and diplomatic missions on account of being able to identify and respect various arms. This eventually evolved into the more recognizable messenger and diplomat and chronicler role that heralds filled, and into the officer that was the King of Arms and the subordinate positions of Heralds of Arms and Pursuivants of Arms.

This position was one of immense prestige, being master over the arms and armory practices of a territory as delineated by the King, most often in the borders of a specific demesne of the lord who held the office. Such territories were termed ‘marches’ by heraldic officers. The King of Arms could also be created for specific chivalric orders such as the Bath King of Arms, who was also considered as the preeminent King of Arms for England. Many Kings of Arms were created and many for different regions of the kingdom. A selection of historical titles, hereditary along with the lordships attached to them, include Windsor, Lancaster, Richmond, Gloucester, Aquitaine, Leicester, Clarenceaux, and Norroy, those last two being the most ancient and expansive of King of Arms purviews.

The specific duties of these officers concerned all manner of armory. Kings of Arms, within their assigned marches, held supreme authority as derived from the Crown over the numbering of the people, that is, the census, and to appoint and create offices of heralds to oversee the following: officiating treaties of peace and marriage between lords and princes, to be present and witness to marital events, to represent their assigned lords by the wearing of proper arms at all events, tournaments, and gatherings, and to record the deeds and happenings of their lord and in their lords lands. Kings of Arms, and their officers, received a bounty of coin for events they would officiate and be present at, such as 100 pounds sterling at the coronation of a king, or 40 marks (64 pounds) when the son of a king was knighted.

To be further expanded