Excerpts from: Customary Law in Rural Hlenderia in the 21st Century

Deranamat Nelvani

About the Author: Deranamat Nelvani is Senior Professor of Anthropology at Thanelen University, College of Sapient and Social Sciences. He is also a Chair of the Research Unit of the Institute of Hlenderian Social Studies and a board member of the Institute.

1.1 Abstract: This research provides an overview of the application and practice of customary law in rural Hlenderia in the 21st century. A qualitative approach with interviews, group discussions, and situational observance was used. Research was conducted in three majority-Mūni towns in northeastern Hlenderia. Challenges and opportunities facing Mūnim today include the effects of climate change on traditional ways of life, the construction of new infrastructure in their land by government workers, and the introduction of the Internet to their previously isolated communities. It is suggested that Mūni communities may benefit from greater representation in the country’s central government, and that adoption of Mūni styles of problem solving may drive efficiencies in the practice of mainstream criminal justice.

[…]

2.3 Methods:

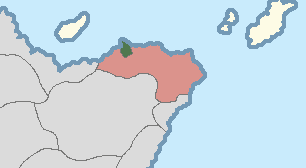

Study area description: Pasika peninsula is located in northeastern Hlenderia. It is designated a Mūni Ethnic Area by the central government and is divided into clans that share the same dialect, traditions, religious practices, lifestyle, and customary law. Clans serve as local administration and facilitate collaboration between families. On the Pasika peninsula, Mūnim carry out subsistence farming and fishing, especially of local salmon. The central government rarely interferes directly in this region. The last direct enforcement of national law on Pasika was in 1987, when gendarmerie were sent in to resolve a local feud over fishing territory rights. Censuses, occurring every five years, are the most common interaction with the central government that Pasika residents have.

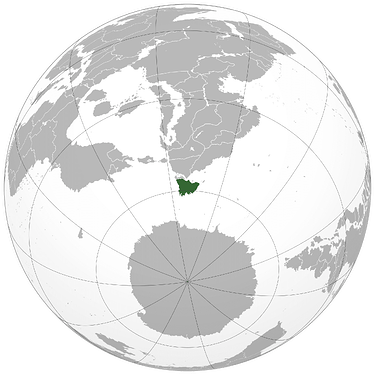

Map 1: Hlenderia situated in the far south of Gondwana

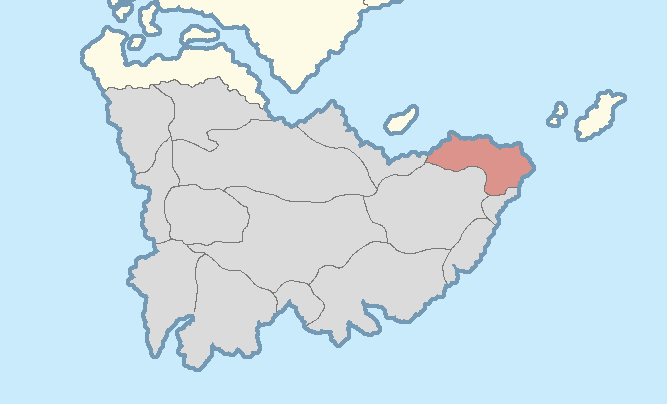

Map 2: Nachiru Province in northeastern Hlenderia

Map 3: Pasika Peninsula (green), where research took place

[…]

3 Results:

The use of cultural values and unwritten codes to regulate social relationships:

Sharrī is the local word for an oral tradition of customary law that regulates relationships between people, families, and clans. The Mūnim live in a culture of honor, and poor conduct can reflect on an entire family unit (Drenni, 1996). Cultural values on Pasika include “righteous action”, which refers to proper conduct in business and social relationships; reciprocity, where individuals act in kind to one another, such as through the mutual exchange of gifts; inviting members of neighboring clans to family weddings and funerals; and “avenging honor”, resolving slights through fines or, rarely, interpersonal violence.

Drenni observed in 1996 that, following government campaigns to reduce “blood-avenging”, the use of fines to resolve disputes increased. On Pasika, the researchers observed one such instance.

[…]

3.3 Chassanisu:

As in many cultures, the treatment of guests is valued on Pasika, and is termed chassanisu - “guest-welcoming”. A member of the Bernūnis clan told the researchers:

If one of our clan members were to travel a long way from their home – for instance, to trade with

another clan who had just returned from the city – they would expect to be fed by their hosts when

they arrive at their destination. The principle of reciprocity would demand that, if the roles were reversed, the host could expect to be fed at our own home. [Male 5, 62 years old, Bernūnis Hill area]

Hospitality is considered a socio-cultural necessity on Pasika. If a clan refused hospitality without good reason, the offended clan could demand satisfaction in the administration of fines. In such an instant, all the regional clans would send a representative to a customary court to rule on the issue. In the past, poor hospitality could be grounds for a blood feud (Yūnrith 2004), but in the modern era fines are widely accepted substitutes across the country.

The same interviewee said:

Guest hospitality allows clans to become friends, and can facilitate marriages between eligible young people. They foster mutual trust and many families have united through marriage and descent as a result of a good host generations before. [Male 5, 62 years old, Bernūnis Hill area]

3.4 Tatu Puchi:

Tatu Puchi refers to traditional gift exchange. Gift exchange is conducted between individuals, families in a single clan, or between clans, on a variety of occasions. Births, weddings, and deaths mandate gift exchange: first, to the affected party, and then, within three months, to the gifter. Gift exchange also occurs to symbolize the end of a dispute, as detailed by one woman:

A family within our own clan, but living across the river, gave us a gift of smoked salmon as an apology. One of the children in their family inadvertently injured my nephew. Because it was accidental, our family would not have been entitled to a fine, but the family across the river took responsibility in an honorable fashion. [Female 2, 36 years old, Tall Trees region]

[…]

3.8 Nisukwaral

Nisukwaral refers to inviting local dignitaries to a familial wedding. A number of rules govern this custom, depending on the role of the couple to be engaged in the community, the role of the parents of each individual to be wedded, and the status of the clan in regional relations. Attitudes towards same-sex marriage vary across Hlenderia depending on local customs. On Pasika, researchers were invited to a wedding of two local women:

It is a sign of very righteous attitude to invite a non-Mūni to a wedding. As I understand, it was Pasri-tat who wanted to invite you. Being that her bride’s family was engaged in a dispute with a Kwari family that moved to Pasika, for you to be invited is a sign of great magnamity. [Female 4, 27 years old, Tall Trees region] [Note: three members of the research team were of Kwari descent.]

Inviting outsider Hlenderians is a occasionally seen among the Mūnim, who use it to demonstrate their worldliness and generosity. Inviting foreigners to a wedding is even rarer, and can easily cause a family to suffer ostracization from their community if not handled correctly.

[…]

3.14 Use of fines as social control

If one of these customs is deliberately disregarded or violated, it is considered a mark not only on the individual who committed the transgression but their family and, if it is severe enough, their entire clan. The most serious offenses are murder, and the murder of guests is considered especially heinous. At one dinner, researchers were told of an instance of guest murder that occurred in the 19th century, and remained a cautionary tale on Pasika to this day.

Traditionally, murder calls for the blood of the perpetrator. If the family of the perpetrator refused to accept the involvement of their own in a homicide, their execution could cause a blood-feud to break out. In this manner, entire bloodlines were wiped out in the past through the actions of two families who could not bear to lose honor by admitting wrongdoing (Yūnrith 2004).

Feuds could also arise when one family could not afford to pay the traditional fine, and so, in a bid to avoid losing honor by dropping the the issue, the offended party would maim or kill someone to achieve satisfaction.

King Randris in the 1980s, and the current King Yendrin after him, have promoted policies and initiatives to eliminate blood feuds in rural Hlenderia. One of these policies involved representatives of the government promoting the use of fines to resolve conflicts, by using government loans to clans that were required to pay a fine but could not afford it. This effort has been criticized as a waste of taxpayer dollars by some on the right, but since its introduction the number of feuds has declined.

Fines are levied on Pasika in accordance with the seriousness of the crime. Accidental offenses carry the lowest fines, and serious, intentional violations of the sharrī legal code carry the highest. In the case of murder, local government authorities are to be called, but rumors of customary tribunals executing murderers persist.

[…]

5 Conclusion

This study of Mūni customary law did not, and cannot, cover its application in all instances. However, the use of deep interviews with Pasika locals shined a light on a number of customs that were previously unknown, or only dimly known, to outsiders. Challenges towards the continuance of this lifestyle are many, including the intrusion of the modern world on these traditional ways of life. Takeaways include the knowledge of what these challenges are, in the Mūnim’s own words, and possible ways to approach them.