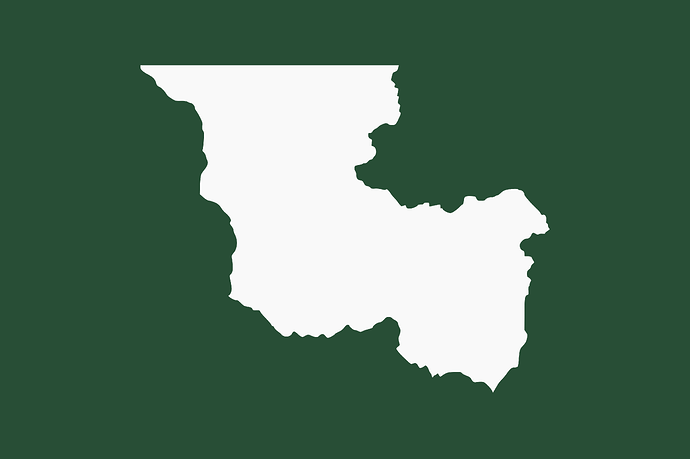

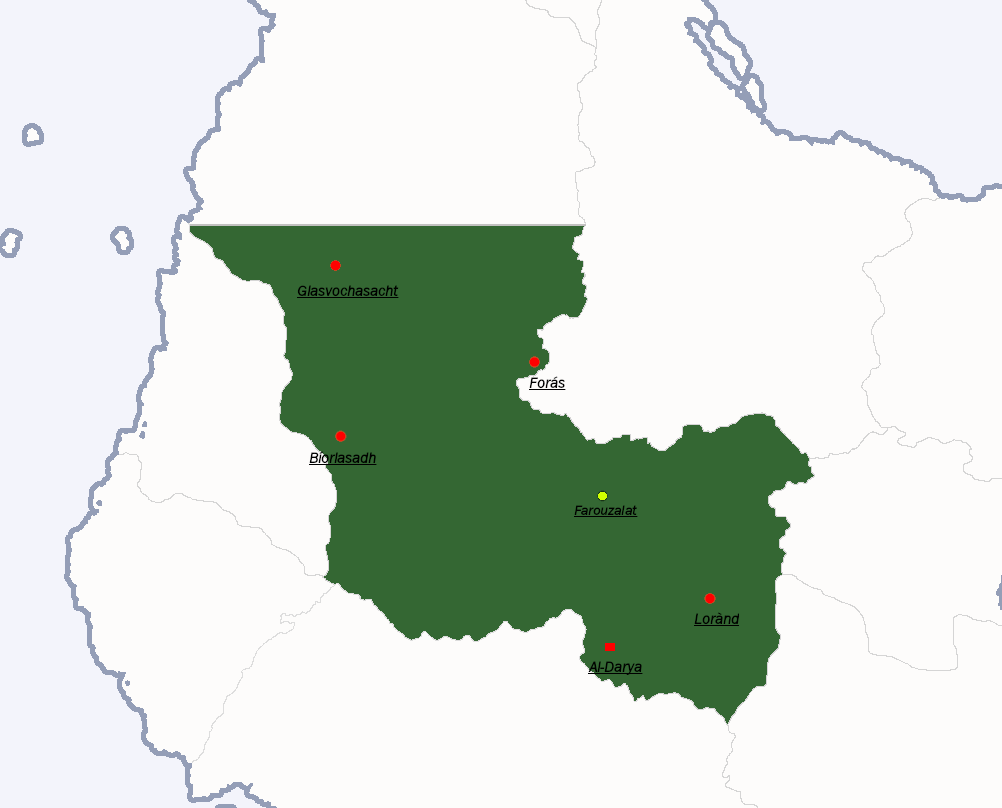

Nation Name (long): West Gondwanan Railway Zone - Réigiún Tiniligh Gonduána Iarthair (Fefsen) - Muqataeat Gharb al-Watania Lilsikak Alhadidia (WGIL-72 Alsaayqayidu)

Nation Name (short): Meilaftaland - Madhlúbháil - al-Malafaghrib

Motto: None official

National Animal: None official

National Flower/Plant: None official

National Anthem: None official

Capitol: None specified de jure. Farouzalat de facto

Largest City: Farouzalat

Demonym: Meilaftish (adjectival), Meilaftalander (person), Malafagriba (archaic, person)

Language: None official. Fefsen and Alsaayqayidu most commonly used

Species: Majority humans and elves. Large dwarven and animalpeople populations, mostly migrants and foreign workers.

Population: 28,490,153 (2023)

Government type: Unitary parliamentary republic under a provisional government

Leader(s): Vacant. All executive powers currently exercised by the Emergency Caretaker Council.

Legislature: Universal Congregation

Formation:

- 28/05/1922 (Aksdaler Arbitration, formal establishment of the Zone)

- 11/03/2023 (Provisional government assumes power)

Total GDP: $808.1 billion (nominal, Q3 2023)

GDP per capita: $28,397 (nominal, Q3 2023)

Currency: Mirhaimian inter

Calling Code: +116

ISO 3166 code: QV/QVV (temporarily-assigned code)

Internet TLD: .qv (temporary)

Historical Summary:

Historically a crossroad of civilizations, the place which the Atasiqayidu of then named al-Malafagrib was, for the past few thousands years, under the control of the old Sultanate of Sayyed, though their power only encompassed the canvas carrying the tughra of kohl-eyed emirs, gold-cladded tax collectors and the red-robed janissaries patrolling the caravanserais. As dry and inhospitable as it may seem, wealth of unimaginable scale moved to-and-fro its unending dunes, carried by caravans stretching as far as the eye can see on routes trodden since times immemorial.

Despite the treachery of a life prowling its sands, many have carved their existence out of those very same deserts, from descendants of ancient Salaharkeshite settlers, bellicose Ashurian and Xuhari nomads, lively Sha’aidari caravaneers to Haqmi transients whose camel-drawn carriages form mobile cities that hop from oasis to oasis prior to the founding of settled civilisation there. These disparate groups existed in a state between chaos and harmony for millennia, the desert providing livelihood as well as protection against Sayqidi authority, an implacable which even the greatest Sayqidi sheikhs and sultans have broken their fortunes and influence on taming.

As unchanging as it was, even as dynasties rose and fell around it, the shifting of times finally came in 1880, when a pride-filled Marishan kahina fatefully rose to defy Sayqidi rule in the north. There, for almost four decades, an exhaustive war was waged, bringing with it suffering immeasurable as vaunted warrior kols rose and fell in tireless battles against hardened imperial infantry. But yet, through it all, the first seed of change for the desert came in the form of a small Khor Sha’aidat-based railway company, formed just years prior to the kahina’s revolt.

The brainchild of a Sayqidi visionary whose kol no longer exists, that seemingly insignificant enterprise quickly came upon royal favor as the revolt grew in size and capability, the then Sultan eager match the rebels blow-for-blow by tapping into the potential for rail-transported supplies and troops through the desert and directly to the frontlines. Throughout the next few decades, the company expanded their rail lines to encompass all of Sayyed and the Anabat Desert, connecting Khor Sha’aidat to Al-Salarqa, and from Al-Salarqa to every other major regional capital city except Kilaz. Even as Sayyed eventually lost Marisha to the rebels in 1918, the importance of the desert railways had soon overshadowed its Sayqidi origins. With the unprecedented scale and efficiency brought by their trains, the Royal West Gondwanan Express Company had become the most important artery of commerce in the entire region.

However, that success had also brought with it unwanted attention.

In Novaris, the Mirhaimian West Gondwanan Economic Company had grown to greatly covet the rail lines that now spanned Sayyed and its neighbors, having not inconsiderably aided in their construction years prior. Correctly sensing al-Salarqa’s weakness in the aftermath of its defeat, WEGEC wasted little time in cornering the new Sultan with increasingly unequal terms. Their economy in shambles, their armies shattered, and themself well aware of the fact that Sayyed would not survive a Marishan counter-invasion without Mirhaimian support, the Sultan eventually relented to WEGEC. In the Aksdaler Arbitration of 1922, Sayyed formally relinquished oversight over the West Gondwanan Express to Mirhaime and privatized the Royal West Gondwanan Express Company, which itself was quickly bought out and incorporated into WEGEC. The entire desert region in which the railways ran through was to become the basis of its own fully sovereign polity, nominally to act as a buffer state between Sayyed and Marisha, yet entirely under WEGEC’s purview.

Thus began the West Gondwanan Railway Zone.

Corporate rule in Madhlúbháil, as the Mirhaimians called Meilaftaland, was backdropped by a distinctly “civilizing” attitude which took hold of the upper echelons of its leadership. Much of it was driven by developments back in Imirodraeth shortly after the Zone’s creation, where Realm-Leiadh Aodhan Alor had tightened his grip on power from chauvinistic populist to personalist dictator. He soon found a powerful support base within the executives of WEGEC, and it was not before long that the rest of Mirhaime too was swept in the colonial fervor. Alor, for his part, was well aware that Mirhaime’s image as master of Western Gondwana hinged upon the Zone’s economic as well as “moral” success: an indivisible display of the technological and cultural triumph of the Mirhaimian empire over Gondwanan “irrationality” which had held the desert back from achieving true development.

To that end, WEGEC was given the blank check to embark upon a project which would come to redefine the very desert itself. By swelling its population with an influx of foreign labor, intermixing and blending them with the original inhabitants until their miscegenated descendants numbered in the tens of millions and outnumbered the latter by a factor of four to one, and by wielding their near-infinite line of credit from Aksdaler and Imirodraeth to fund infrastructure of unprecedented scale, from underground waterways and bullet trains and sapient-made lakes to massive urbanization projects which brought the metropolises of the Novaran and Concordic kind to a region previously devoid of it; WEGEC sought to break powers that be, and remold them in its image. One by one, the hallmarks of the desert fell victim to the march of corporate change: the caravans, former beating heart of commerce, rendered obsolete by the middle of the century when the railway tracks became cheap and numerous enough for even the most benign uses; their nominal protectors, the warbands of the Xuhari and Ashurian nomadic confederations, destroyed in a series of campaigns carried out by WEGEC’s own security forces in the early days of the Zone, their paramounts forced to submitting and subsuming themselves into the corporate leadership in a begrudging effort to retain their rights; and the ancient settlers, the Meilaftish Atasiqayidu and Salaharkeshites, displaced from their own lands by corporate encroachment, their date farms and pastoral grounds used to raise the cities and the numerous mines from which the wealth of the Zone were extracted, and with which the trains carried to everywhere and anywhere WEGEC’s customers needed them to.

By the end of the old millennium, so successful and total had the WEGEC project been that it would be remiss to call it anything less than terraforming. From what had been a small and humble railway company in Khor Sha’aidat, WEGEC had transformed into the lynchpin of the most extensive developmental project in West Gondwanan history. One which created cities and fertile farmlands and massive mines out of near-nothingness, one which brought its defiant inhabitants to heel, one which turned a desolate region into one of the strongest economies in the Western Hemisphere.

In less than a century, WEGEC had achieved what none of their predecessors could in the better part of a thousand years: they had tamed the desert.

Yet, for all its success, that achievement belied its invisible cost.

Though his reign lasted for only 20 years, Aodhan Alor’s legacy lived on in Gondwana, and it was his ideology which would come to haunt the Zone. The natural hierarchies, the demonization of heterodoxy, the stratification of society for the sake of social “harmony” and the implacability of a learned elite in upholding that structure; all ideals espoused by Alorism, all put to practice in the Zone just as it had in Mirhaime. But, unlike in Mirhaime, where the institutional changes he sought to affect Mirhaimian society were promptly repealed without rancor, none such roll back was forthcoming in the Zone. And unlike other WEGEC-controlled protectorates such as Aldaar, that very ideology had become ingrained in not only the corporate executives and their dynastic descendants, but within the very lower classes they oppressed.

By the start of the new millennium, the Zone had become a bloated creature. Decades of societal rot were left untreated, its lower classes pushed to borderline slavery and their identities pitted against each other by an elite who had siphoned whatever was left of their future for their own use, who had gotten away with it by insulating themselves to the point that municipal means of criminal investigation no longer affected them in the long-term, who treated them more as indolent animals to be whipped into shape as cogs for the corporate machine than as sapients, and who had it so that that very line of thinking was to be internally perpetuated in the working people by their familial elders, who had by then found solace in the shadow of their deeply stratified system. Grew the economy did, but it became clear that growth was built upon a fragile house of cards.

One which was bound to collapse, came the indictment of the entirety of the West Gondwanan Economic Company by the Mirhaimian court on charges of corporate espionage, embezzlement, and of crimes against humanity; came March 11th, 2023.