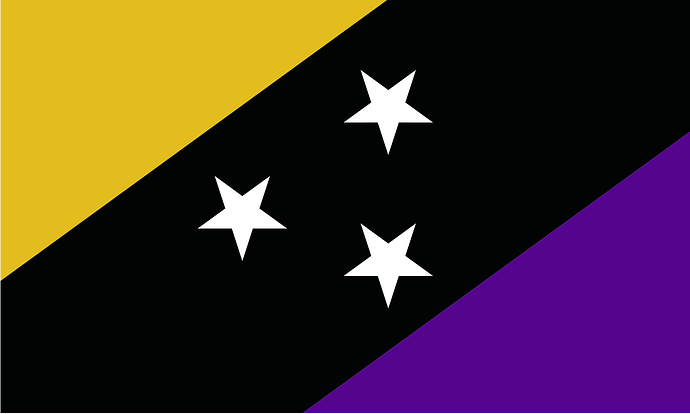

Flag:

Nation Name (long): Sovereign League of Vakani Dalar (Staynish), Kraníkar Eretavi Vakani Dalar (Tavari), Gahamiah Oidai Bagai-Dalah (Xoigovoi)

Nation Name (short): Vakani Dalar

Capitals: Xoi (legislative seat, metro area pop. 3.7 million), Tana-Mota (executive seat, metro area pop. 4.1 million), Tažnatta (judicial seat, metro area pop. 1.9 million)

Largest City: Tana-Mota

Demonym: Dalarašta

Language: Tavari, Xoigovoi

Species: 93% orc, 5% human, 2% other

Population: 27,820,258

Area: 148,339.69 sq. km. (23,393 px)

Government type: Loose confederation of three members: Xoigovoi, Vonatan, and New Tavaris. Each member of the League is itself a federation of semi-sovereigns.

Leader(s): Debra Boimah, President of Xoigovoi; Lešteren Novar Kenetta, Prime Minister of New Tavaris; Ratoni Memza Babasi, Grand Elect Brother of Vonatan

Legislature: Common Council (confederation-level policy making body), Senate of the Isles (a joint sitting of the three “legislative authorities” of the members of the League, as defined by the members’ own laws.)

Formation: Independence from Tavaris in 1792 as two independent countries of Vonatan and Xoigovoi. Vonatan Civil War 1798-1803, New Tavaris formed in 1803. Confederation in 1910.

Total GDP: $357,212,112,720

GDP per capita: $12,840

Currency: Vakani Dalar Našdat (VDN, ŋ)

Calling Code: +116

ISO 3166 code: VD, VDR

Internet TLD: .vdr

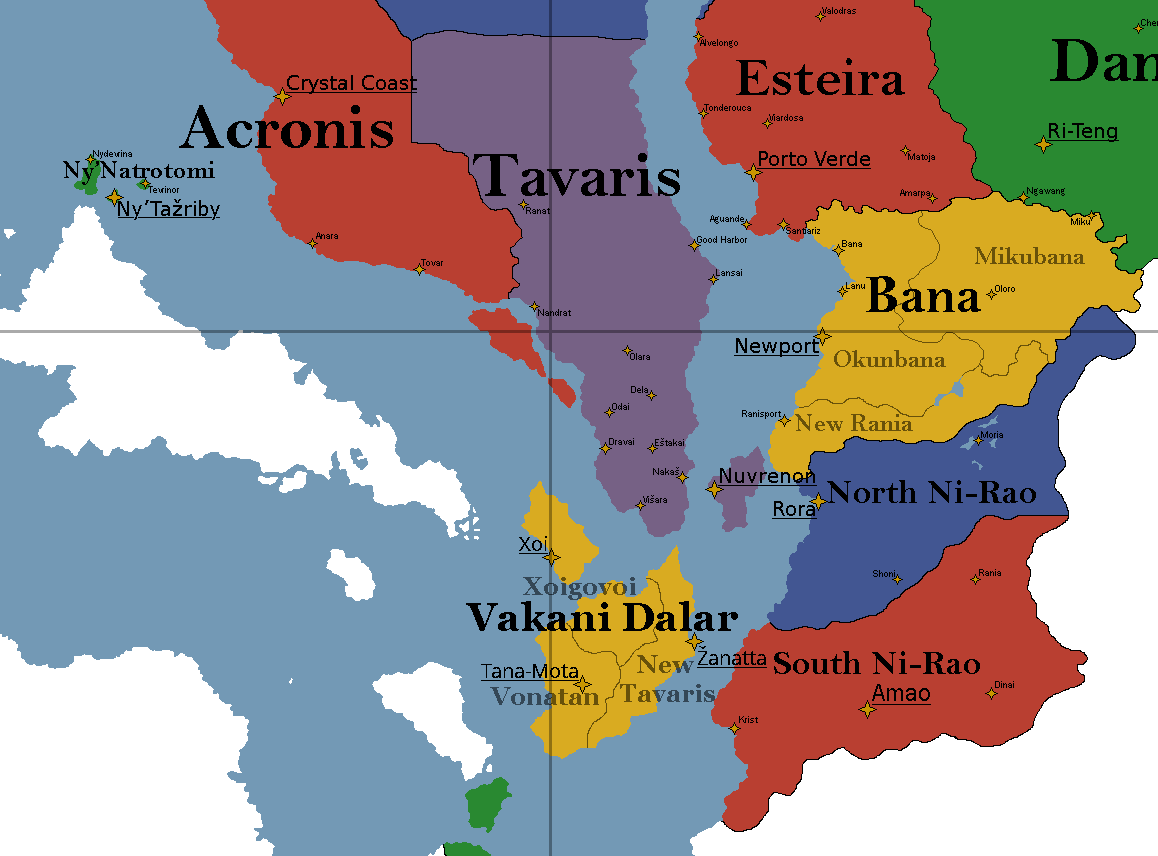

Map:

Note to Cartos: Attached is an XCF file for the border shape for your convenience, but something appears corrupted about my fonts in GIMP, so don’t copy over any text from the file.

Vakani Dalar.xcf (207.9 KB)

Historical Summary:

Vakani Dalar consists of two islands: Xoigovoi (pronounced “CHOI-go-voi”) to the north and Avonata to the south. These islands are collectively known as the Southern Isles (in Tavari: Vakani Dalar.) Both of these islands have been inhabited by peoples believed to be closely related to the Tavari since before written records began. Xoigovoi is home to the Xoigovoi people, who speak the Xoigovoi language. The natives of Avnonata are the Vonatani, an archaic Tavari word for “cousins” (no longer used because of its association with the ethnic group) so called because of their close relation to the Tavari people. The Xoigovoi language is a Tavaric language, indicating a similar but more distant relationship between the Xoigovoi and the Tavari. All three groups ultimately descend from the same exodus of the Tapar people from the Danvreas in 504 BCE.

There was considerable contact between the Vonatani and the Tavari over the course of their early history, evidenced in their language—the Vonatani dialects exist on a continuum with Tavari, some but not all of which are even mutually intelligible. Both groups developed similar traditions of ancestor worship that seems to have evolved from an older tradition of animism, though it is debated whether the Vonatani religious tradition is the same as the Tavari Tavat Avati. Both groups also came to divide their societies into clans. Like most Tavari lines, Vonatani clans tended to elect their leaders—known as Votroni, or “Brothers,” irrespective of gender—but unlike Tavari lines, were often defined by some means other than family ties. Whereas Tavari lines were always defined by common descent from some individual, Vonatani clans could be formed for any number of reasons; many were hereditary in nature, but others were defined by geography, trade, or simply as a voluntary group of unrelated people seeking protection and companionship. Vonatani society was always highly fragmented and hyper-regional, with few examples of individuals or clans ever coming to significantly dominate over the others.

While the Vonatani are undeniably closely related to, and share many similarities with, the Tavari people, it is certain that no Tavari chief ever held true political control over any of the Vonatani prior to the unification of Tavaris by the Chiefs of Nuvo in 1304. While there may have culturally been a degree of ambiguity, legally and politically speaking, the Vonatani were not considered to be Tavari.

Xoigovoi remained much more isolated from the Tavari. Their similar language is the only immediately obvious hallmark signifying their common origin. The Principality of Xoigovoi formed in the early 12th century and from early on presented itself as a rival and opponent to the Chiefs of Nuvo, who by that time were beginning the Unification Wars to consolidate their control over the disparate Tavari chiefdoms. Xoigovoi was rich in both iron and gold, and even early on they had a reputation for powerful warriors. Xoigovoi mercenaries were important parts of the contingents on both sides of the Unification Wars; the Chiefs of Oren in modern Motai province fought off the Nuvo yoke for decades with armed forces composed primarily of Xoigovoi fighters. The Chiefs of Nuvo themselves contracted with several Xoigovoi mercenary companies, and even after unification, such groups seeking payment of debts (either real or claimed) from the Nuvos were often able to attain permission from the Princes of Xoigovoi to harass Tavari ships and even, at times, raid the Tavari coast especially around Višara and Dravai.

In 1349, Xoigovoi launched an invasion of Avonata and began to settle in a region on Avonata they came to call “the Plantation.” The Vonatani reached out to Tavaris for aid, and newly enthroned King Utor IV—annoyed by Xoigovoi pirates and raiders, and seeking to ensure Tavari supremacy over their Xoigovoi rivals—agreed to send troops to repel the Xoigovoi invaders. While the Tavari had seen success in repelling overextended Raonites from King’s Island earlier in the century, initially the Tavari struggled against the generally wealthier and better equipped Xoigovoi. The Xoigovoi Wars continued off and on throughout the reign of King Utor IV, who died in 1360, and Utor V, last of the first dynasty of Nuvo monarchs, who died in 1369. It was not until Queen Anadra I took the throne that the Tavari fortunes began to turn—after the Queen, seeking to entrench her power and claim to the throne after being the first of a new family of Nuvos to assume the monarchy, devoted a much greater share of wealth and resources in financing the war effort. Queen Anadra also devoted time and effort into making the Xoigovoi Wars a project of nation building, encouraging her soldiers to carry Tavari flags into battle and deliberately placing groups of soldiers from different parts of the country together in order to build camaraderie among Tavari from different regions. The Tavari national motto, “Ítan Erevat, Ítan Eredan!” (“For the King/Queen! For the State/Empire!”) was originally a battle cry that Queen Anadra encouraged her soldiers to shout as a unifying call as they charged.

In 1377, a settlement (the Peace of Višara, after the city where it was signed) between the warring parties ended the war, but allowed the Xoigovoi Plantation on Avonata island to remain as part of Xoigovoi. In recompense for Tavari service in the war, the Vonatani—represented by a coalition of the most powerful Vonatani leaders called the Council of Brothers—permitted the Tavari to settle in Vonatani lands. From that point onward, there was an almost constant stream of immigration from Tavaris, and almost immediately, Line Nuvo began to plan an expansion of Tavari political and military power into Vonatan. The town of Tažnatta, meaning “distant court,” was established by Queen Anadra as a base of Tavari expansion and as a stream of revenue for the royal family.

The Council of Brothers disintegrated shortly after the war, lacking a common impetus that gave them an incentive to set aside their political disagreements. Tavari chiefs began to reach out to Vonatani Brothers, forming alliances that helped bolster the capability, strength, and wealth of Tavari chiefs but further fragmenting Vonatani unity. While the Tavari chiefs’ capacity to expand their own land holdings, and thus wealth and power, in Tavaris were limited by constraints enforced by royal authority, in Avonata they were virtually unchecked so long as they remained nonviolent—and even this exception had loopholes, as while the Peace of Višara enforced limits on land claims by the three parties, it had nothing to say about violence among and between the Vonatani themselves, leading the Tavari chiefs to fight proxy conflicts over land and resources in Vonatan through their allied Vonatani clans.

The first half of the 15th century in Tavari history is characterized by a focus by the Tavari government on affairs in the Southern Isles, to the detriment of other areas at the fringes of Line Nuvo’s control, primarily the more distant frontier regions of western Tavaris. Some historians believe this is part of the reason why Akronism was able to take hold in western Tavaris in the middle and later decades of that century. In the 1420s, Vonatani clans began to protest continued Tavari expansion and some even began campaigns of violent skirmishes and raids of Tavari settlements on Avonata. An attack on Tažnatta in 1421 started a fire that burned down a quarter of the city, and this was enough for Tavari Queen Doreš I to declare war on the Vonatani.

The Tavari-Vonatani War was fought from 1421 to 1428 and ended with Tavaris annexing the eastern coast of Avonata. The Tavari had outright naval supremacy but struggled in making inland gains, unable to hold any of the Vonatani strongholds in the southwest, where the Vonatani population was most dense. While the war resulted in Tavaris gaining a significant expanse of new territory, it firmly established the Vonatani as Tavari enemies, and pushed the Vonatani and the Xoigovoi into an anti-Tavari political and military alliance. Relations between Tavaris and its southern neighbors would remain tense and periodically violent for the next few decades.

From the 1470s through much of the 1490s, significant unrest broke out in western Tavaris due to the rise of Akronism. This new faith taught a highly egalitarian philosophy that said that distinctions like clans or lines, or like chiefs and kings versus commoners, ought to be avoided and that everyone was equal in the eyes of Akrona. Akronism, while held as extremely suspect among the political elite, was popular among the common people, who cited it in increasingly forceful demands for political reforms. A movement known as “Line Akrona,” with its adherents forswearing any allegiance to any of the 1,152 established Tavari lines but instead only to Akrona, Akronism, and one another, was viewed as such a threat by Tavari authorities that Kings Vonar I (r. 1479-1490) and Zaram I (r. 1490-1496) engaged in military campaigns intended to forcefully quell Akronist demands for change and to silence Akronism as a political force.

When King Kanor I (later known as Kanor the Great) took the throne in 1496, he took a different approach to the Akronists. In addition to encouraging Akronists to settle in Metrati Anar, then a private holding of the royal family, he drafted Akronists—especially those arrested for committing crimes—into a military effort to conquer Avonata. In an echo of Queen Anadra’s nationbuilding in the Xoigovoi Wars, King Kanor deliberately involved Akronists in military campaigns undertaken in the name of Tavaris in order to connect the Akronists to Tavari identity and to Tavari ideals. By including Akronists in the campaigns for Tavari expansion, he accomplished his own political goals while also ensuring the Akronists a place in Tavari society in which they could exist largely on their own terms. This, in addition to Kanor’s abandonment of efforts to entirely eradicate Akronism, assured the continued existence of Akronism and also set the stage for the faith’s central role in later Tavari expansionism.

The Avonata War was fought from 1498 until 1503. Officially, the causus belli for the war was a Xoigovoi attack on a Tavari ship, but modern historians tend to consider this a pretext for a war that Kanor had already decided he wanted to undertake for reasons of expansionism. Kanor stated quite clearly at the outset that his only goal was “the absolute and total subjugation of the entire Southern Isles.” Bolstered by thousands of Akronist draftees as well as knights and other warriors who had until recently been otherwise occupied in western Tavaris, and engaging in harsh, total war-like tactics, Tavari forces decimated Vonatani troops and, while initially struggling, eventually outlasted and overcame the Xoigovoi as well. Tavari troops captured Xoi, the oldest and one of the grandest cities in the islands of the Gulf of Northwest Gondwana, and burned it to the ground in 1503, and shortly thereafter the Prince of Xoigovoi and an assemblage of more than a hundred Vonatani Brothers signed the Articles of Surrender that formally annexed the Southern Isles into the Kingdom of Tavaris. Many historians consider this moment to begin the era of the “Tavari Empire.”

After the annexation of the Southern Isles, Tavaris began to undertake a campaign of erasing the unique cultural expressions of its residents. Officially, Vonatani clans were abolished, and the Vonatani were required to swear allegiance with one of the Tavari lines. And while Line Nuvo assumed the property, incomes, and other wealth of the Xoigovoi royal family, it refused to use the title Prince of Xoigovoi and proscribed the symbols and traditions associated with it from being used. Both of these, however, caused significant resentment and unrest among the population, leading to continued violence against Tavari rule. In 1524, King Kanor II appointed Talu Bronai, the wealthiest and most politically powerful of the sons of former Vonatani Brothers, as Prince of Xoigovoi, which he refashioned as a sort of political deputy and viceroy representing the royal family in the Southern Isles. This generated significant conflict between the Xoigovoi political elite and the Vonatani political elite, pitting them against one another, but earned the Tavari authorities a powerful ally. Kings of Tavaris would continue to appoint Princes of Xoigovoi in this manner, usually from among the Bronai dynasty, until the mid-18th century.

Already by the early 16th century, the eastern portion of the island of Avonata had become known as “New Tavaris,” as a result of the concerted campaign of Tavari settlement and expansion into this area since the early 1400s. New Tavaris was by far the most peaceful and easiest place in the Southern Isles for Tavari to settle; the Tavari language and culture became dominant there and the Tavari population was believed to form a majority by 1550. In comparison, ethnic Tavari settlement in the Xoigovoi Plantation was much less established, and almost non-existent on Xoigovoi island and in the region of southwestern Avonata which came to be known, as a back-formation from the name of the Vonatani who comprised the overwhelming bulk of its population, “Vonatan.” (In the Tavari of “mainland” Tavaris it would be “Vonatanis,” but this suffix is less entrenched in dialects of Avonata.)

The Tavari line system became established in both New Tavaris and Vonatan, but especially so in New Tavaris, the only place in the Southern Isles where Tavari chiefs truly fully legally and financially integrated their land holdings with their holdings in mainland Tavaris without having to involve intermediary legal processes or institutional holdovers from previous Vonatani legal regimes. For example, while the Vonatani clans were nominally unrecognized, they still held considerable de facto power in their former areas of control and often controlled the local financial systems and artisan guilds, requiring a degree of deference to their traditional laws before lowering these barriers to Tavari entry in their regions.

In contrast, Xoigovoi—whose society had never been divided on clan-based lines—resisted a switch to Tavari line-based governance. Officially, like all Tavari, the Xoigovoi were expected to pledge allegiance to a Tavari chief and adopt a line name. In practice, few did, and the Tavari chiefs were never able to enforce their customary property and law enforcement rights in Xoigovoi-majority areas. The existence of “unchiefed Tavari,” meaning Tavari citizens who were not subjects of any of the chiefs, was a legal gray area that presented significant law enforcement challenges. The Tavari monarchy’s ability to levy soldiers depended on chiefs to do the actual work of gathering men and women from among the households loyal to them. Taxes were often collected by chiefs as well. Without intervening chiefs, the Tavari monarchs came to depend on the Prince of Xoigovoi to act as a de facto “chief” of “Line Xoigovoi,” which empowered the Princes at the expense of the Tavari monarchs.

The delicate and precarious balance of nominal Tavari control in the Southern Isles based on varying degrees of acceptance of underlying informal Xoigovoi and Vonatani political influence systems continued for more than two and a half centuries. However, as Tavaris gradually expanded over the course of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, becoming militarily and administratively responsible for greater and greater swathes of the globe, cracks began to appear. In 1754, King Kanor VI appointed the young Nonatalu Bronai, 20 years old, as Prince of Xoigovoi, the first Bronai Prince of Xoigovoi in more than fifty years, in part in an attempt to earn the favor of the Bronai dynasty and encourage a higher rate of tax collection. He likely chose a young candidate out of a belief he could be more easily influenced. While he initially complied, he soon came under the influence of a social and political movement among Xoigovoi people, especially Xoigovoi political elites, opposing the Tavari due to a growing sense of systemic exclusion by Tavari institutions and society.

At the same time, Tavari monarchs had for centuries by that point been attempting to reduce the power of the Chiefs in favor of centralized administration by the monarchy. The legal powers of the Chiefs had indeed waned since the 14th century, but the approval of the Chiefs was still de facto required for the monarch to levy taxes and raise armies. In 1757, Kanor VI announced a change to a professional, standing army—thus eliminating an area of leverage the Chiefs had over the monarchy to extract concessions in order to deliver troops. As part of this change, it became illegal for Chiefs to maintain their own private militaries, as they had done since time immemorial. This was unpopular universally, but especially in Xoigovoi, where strong soldiers had become part of their cultural identity, and where a large army loyal to the Prince of Xoigovoi was a far more beloved institution than the Tavari monarchy.

Initially, service in the new, professional Royal Tavari Army (or Navy) was treated like a government sinecure and used to dole out favors and honors. Around this same time, knighthood in the Amethyst Order transitioned from being a functional military role to an honors system. While this helped to quell early dissent and ease the transition, it was not long before many—especially in Xoigovoi—began to resent the control the Tavari national government exerted over the military, especially in how it deployed soldiers often far from home and paid little respect to the wishes of Chiefs to treat their favored heirs with lighter or more prestigious treatment, both contrary to norms established after the end of the Fourth War with Bana in the 1680s. Chiefs also resented the obvious winnowing of their political power and began to have existential fears about the continuance of their offices.

In 1784, Tínara II came to the Tavari throne after her mother, Adra I (known as Good Queen Adra) resigned due to health reasons. Adra was popular and her abdication was seen as honorable in stepping aside for someone healthier and more capable to assume governance of what was at the time considered to be by much of the public an increasingly wealthy and powerful intercontinental empire with complex administrative needs. However, Tínara II—45 at the time of her ascension—while not young, had never had surviving children and was essentially certain to die childless. Political observers thus tended to discount her as irrelevant, since she would have little influence over the policies of her heir, likely to be one of her cousins. As her mother still lived and was widely respected, it was also still expected for Good Queen Adra to be kept abreast of state affairs and allowed to give input, which according to court records, she did frequently. Courtiers and Chiefs often preferred to speak to Good Queen Adra than to the actual Queen.

It is in this environment that Tínara II came to believe that she needed to be forceful and powerful to maintain the dignity and power of her office and her own position. Prince Nonatalu of Xoigovoi was particularly vexatious to her; by now, he was considered a leading statesman and a favorite of Good Queen Adra’s, and despite the Prince being only 5 years older than Queen Tínara, this was apparently enough for the court to consider him wiser and more knowledgeable than the "young’ queen. In 1791, Prince Nonatalu began privately meeting with Chiefs to encourage them to impress upon the Queen a need to abolish the professional standing army and return to the system of levies maintained by the Chiefs. He even began to suggest that the Chiefs had a right to decide on this policy themselves, and force the monarch to accept it, based on an understanding that “customary Tavari law”—the unwritten system of conventions that underpinned the informal Tavari constitution at the time—granted the power to maintain and levy troops to the Chiefs, not the monarch, and that the monarch could only call upon the levies in times of war or emergency.

Queen Tínara viewed Prince Nonatalu’s actions as dangerous to her continued authority as well as treasonous. She had him arrested and ordered the Royal Tavari Marshalls to sweep through Xoi and other areas held directly by the Prince of Xoigovoi for evidence of illegal private armies. There were indeed a company of trained soldiers bearing equipment marked with the royal seal of Xoigovoi—a symbol banned by Tavaris when Xoigovoi was annexed more than 2 centuries prior—who were arrested as well. Intended as a show of force, and believing the public would side with her against people accused of treason, Queen Tínara had the Prince and all the soldiers publicly executed. This, however, horrified and outraged the Chiefs as well as many in the public, who found the executions barbaric. (Tavaris had never had a culture of public execution.) Afterward, Queen Tínara announced that she, as Chief of Nuvo, would assume responsibility for all the “unchiefed” in Xoigovoi in the absence of the Prince. This de facto expanded Line Nuvo by millions of people and was seen as a grab for cash and power, another unacceptable violation of the status quo according to the Chiefs.

Violence began to break out in Xoigovoi, which soon spread across the Southern Isles as other groups, especially some of the most resistant groups of Vonatani who adhered most closely to the informal, technically illegal parallel system of Vonatani clans that had lingered since Tavari annexation. By the late 18th century, Vonatani clans were organized more like voluntary associations of people rather than hereditary ones, some of them based around occupations but nearly all of them featuring esoteric, semi-religious rituals that likened them to secret societies. While nominally members of Tavari lines, most Vonatani also had membership in one (sometimes more) of these informal clans. When Vonatani began to participate in riots, Queen Tínara very quickly began to target the clans for arrest—this served only to inflame the politically radical of them to further resist the monarchy.

In January of 1792, a fire burned down a major portion of the Vonatani capital of Relumar. It is unclear who or what caused the fire, but contemporary observers largely blamed Royal Tavari Marshals who were patrolling the city with whale oil lanterns at night, though it does not seem that anyone witnessed, or at least reported witnessing, the break out of the fire. In any case, widespread riots broke out across the Southern Isles in the following days as the news broke, and Queen Tínara declared an insurrection. As was held to be typical in emergencies such as these, Tínara called the Chiefs to summon levies of troops to supplement the Marshals and Army soldiers in the Southern Isles to quell the rebellion. However, for the first time, many Chiefs simply refused to contribute troops to Tínara’s cause, unheard of at that scale in Tavari history. Called the Crisis of 1792, the violent insurrection lingered for most of the year with Tínara unable to quell the rebellion with the number of troops she had at her disposal.

While the Southern Isles remained wracked with violence and out of royal control, attempts to spread the violence elsewhere in the Tavari colonial empire largely failed because of the support of a few chiefs Queen Tínara was able to secure, especially particularly wealthy ones such as the Chiefs of Nevran—long an ally of the Nuvos—as well as Oren, Išdašt, Novar, and a handful of others who all controlled significant swathes of land in both mainland Tavaris and in the colonial territories such as Rodoka, Elatana, and Metradan. While most Chiefs would not send their soldiers to the Southern Isles, enough chiefs responded to riots and peasant uprisings on or near their lands simply out of a need to defend their own property. Chiefs and commoners alike feared an escalation from occasional outbreaks of riots and crime to true civil war between Chiefs. This provided an impetus for Chiefs to seek negotiations to end the underlying political crisis.

The settlement to the Crisis of 1792 was largely negotiated by Good Queen Adra, to her daughter’s great chagrin. (However, Tínara’s own continuance on the throne is largely attributable to Good Queen Adra, who is said to have impressed upon the Chiefs the importance of recognizing the current living head of Line Nuvo as the monarch as a sign of recognizing the ancestral spirits and the Tavat Avati.) As Tínara had simply been entirely unable to bring the Southern Isles under control, it was acknowledged in the settlement that Xoigovoi and Vonatan were to become independent. However, in the remaining Tavari Empire, the office of Chief was abolished, and the Chiefs as a collective institution were replaced by the elected Diet. Chiefs, many of whom were simply elected into the new Diet and enjoyed a more formally defined sense of control in the political system, were largely pleased by the transition to constitutional monarchy and considered themselves the victors of the change compared to the now limited monarchy. Tínara, however, was allowed to remain on the throne and counted the continuance of the monarchy and its theoretical but explicitly textually protected position as ultimate guarantor of Tavari governance as its own victory.

The two independent countries of the Southern Isles, Vonatan and the Principality of Xoigovoi, almost immediately descended into chaos upon independence as they had no formal institutions of leadership prepared to assume the tasks of governance. Obatalu Bronai, the nephew of Nonatalu, assumed the throne of Xoigovoi as Prince after about a year of armed struggle between himself and the hosts of two of his brothers, his own mother, and two unrelated claimants. Soon after, in 1794, he declared himself King of Xoigovoi.

Vonatan took much longer to coalesce. A loose leadership, calling itself the Council of Brothers after the ancient group of Vonatani clans, claimed nominal authority but in reality held little sway on the ground. There were major disputes between the core Vonatani heartland in the west and the region called New Tavaris in the east, which unsurprisingly had a much stronger association with Tavaris and a large proportion of people who sought to return to Tavaris. The ethnic Tavari also sought to maintain the Tavari line system, while one of the earliest stated aims of the Council of Brothers was to restore the Vonatani clan system. The Vonatani clans, however, varied widely in their style of governance and their political ideologies, and found it difficult to agree on much of anything. Civil war broke out in Vonatan in 1798, and ended in 1803 with the independence of New Tavaris. After the departure of most of the ethnic Tavari, it became easier for the Vonatani to form a working consensus, and by 1805, there were regular, well-attended meetings of the Council of Brothers that consisted of representatives of more than three quarters of the Vonatani clans. That year, the city of Tana-Mota (“New Center”) began construction as a planned capital for Vonatan.

Almost immediately upon the creation of New Tavaris, Tavaris sought political and economic influence there. Many Tavari, both elites and commoners, wanted Tavaris to re-annex New Tavaris. A shift in prioritization toward New Tavaris is believed to have played a major, though never publicly admitted, role in the Tavari decision to withdraw from Emerald Coast in what is now north Ni-Rao in 1804. However, despite much concerted effort, Tavaris was never able to secure support either within its own borders or among New Tavari citizens in order to effect re-annexation. Part of this had to do with former Tavari chiefs, some of whom had moved to or moved significant operations to New Tavaris in order to escape oversight and Tavari taxes. The legal position of the Tavari Lines remained unclear in New Tavaris, and many of the former chiefs sought a return to outright feudal systems of holding and administering land. Sizable minorities of Vonatani in New Tavaris also strongly resisted reintegration with Tavaris.

New Tavaris came to be governed as a union of what were called Commonwealths, which were groupings of land based around the major cities of New Tavaris backed by coalitions of Tavari lines, some Vonatani clans, and private companies and landowners who agreed to provide people to the national government to serve as a militia to keep order. These hybrid municipal-clan governments were highly independent of one another, and for several years, New Tavaris had no single national head of state. Eventually a system in which the governments of the Commonwealths elected one of their own to serve as President of New Tavaris was instituted. This was based on a similar system in Vonatan where the Council of Brothers picked one Brother each year to serve as Grand High Brother. Vonatan, too, was governed as a collection of autonomous units, but theirs were much, much smaller, with each clan tending to control land the fraction of the size of the New Tavari Commonwealths. There were hundreds of Vonatani clans, and only five Commonwealths.

In the 1890s, after the Gondwana Straits War that was viewed as a Tavari failure and evidence that the Tavari military had lost its administrative and martial capacity, the Tavari government sought opportunities to shore up the Tavari image and demonstrate Tavari military capability. One such opportunity arose in 1893, when an armed insurrection in New Tavaris pitted the Commonwealth of New Odai against the leading Commonwealth of Tažnatta, home to the capital. In the outbreak of violence, the Tavari ambassador to New Tavaris and his family, along with three other staff in the Tavari embassy, were killed. The Tavari government cited this, as well as the general threat of disorder in a bordering neighbor, to launch an invasion. While the Tavari military was able to secure and hold Tažnatta, other Commonwealths strongly resisted Tavari encroachment, and Tavari troops withdrew in 1894. The embarrassment brought down the government of Prime Minister Bežra Oren Macandi.

While the process took several years, the failed Tavari invasion spooked the three countries of the Southern Isles and began the political process of unifying the three under a single federation. The idea of a confederation between the countries was not unheard of, but had yet to become popular. Each of the three was strongly opposed to making changes to their internal governing structures, and each was wary of yielding any power to the other two. It took the outbreak of the Great War to truly kickstart the negotiations, and even then took until 1910 to complete, after the Asendavian invasion of Tavaris appeared likely to bring down their largest neighbor and threatened to overturn the entire regional order. While the Southern Isles feared Tavari irredentism, they had managed to resist it. The threat of Asendavians, or indeed anyone else, taking control in the region was a complete unknown that the three countries felt presented a threat they were unlikely to be able to face alone.

Since confederation, no military threats against the Isles have materialized. The Tavari position of isolationism after the Great War, especially between the 1920s and 1970s, helped to cool tensions between Tavaris and their southern neighbor. Tavaris is Vakani Dalar’s largest trading partner and, especially since a shift in foreign relations toward inculcating relations on Gondwana beginning in the 80s, Tavaris has reached out with a policy of expanding economic, cultural, and political ties. However, constantly shifting governments within Vakani Dalar have rendered it difficult to maintain anything more than surface-level ties, as successive regimes in each member of the confederation tend to often oppose and overrule commitments made by their predecessors. For example, successive military juntas in Xoigovoi first withdrew from a visa-free travel arrangement with Tavaris in 1982, then pleaded to restore it in 1985, only to withdraw again in 1987. Because the confederal government is strictly disallowed from interfering in how the members determine their own governments, there are few institutional safeguards against coups or other forcible government changes in Vakani Dalar.

The confederal government of the Sovereign League of Vakani Dalar was designed to have as little power over the member governments as possible. It is characterized in its constitution primarily as a defense agreement in which each pledges to defend the other two in the case of an attack. However, each is allowed, and in fact required, to maintain its own separate military, with each only ever operating in the borders of the other members if explicitly invited. Each is allowed to conduct its own foreign relations as well, except in those few areas of law reserved for the confederal government. However, modern conventions of international relations generally mean that most countries only conduct relations with the Sovereign League and not with its individual members except in limited respects. The confederal government is empowered over roads and railways, the postal, power, and telecommunications systems, weights and measures, to enforce the terms of the confederal constitution on the members.

The constitution defines one body, the Common Council, as the decision-making body at the level of the Sovereign League, consisting of delegates appointed by each member’s government. Each can send however many delegates they wish, but there is only one vote per each member. The Common Council is seated in Xoi in recognition of its status as the oldest city on the Isles. However, the constitution requires each of the member capitals to have a “significant confederal government presence,” and so it was decided that the “executive branch” would be seated in Tana-Mota (the largest capital) and the judicial branch—consisting of just one High Court—in Tažnatta. The executive branch, which includes several administrative agencies, is by far the largest branch of the Dalari government, responsible for delivering nearly all confederal government services. A body known as the Senate of the Isles, which is a joint seating of the three member legislatures (or equivalent), is summoned as needed for constitutional amendments and can overrule decisions of the High Court, but is not a standing body.

As of 2023, all three members of the Sovereign League of Vakani Dalar have nominal democracies, though President Brenda Boimah of Xoigovoi, who assumed power after the most recent junta dissolved, has been reelected consistently for nearly 20 years and has essentially outlawed opposition parties. The democracy in New Tavaris is similarly fragile; election monitors routinely report signs of voter fraud, especially in relation to buying and selling votes, which has become relatively common in New Tavaris. Both Xoigovoi and New Tavaris have experienced several coups and other changes in how they govern themselves over the years. Only Vonatan has maintained the same system of governance since its independence—though because its clans are so small and numerous, their own governance is highly decentralized, and clans are under no obligation themselves to be democracies, meaning a sizeable minority of Vonatani do not elect their representatives either at the member or confederal level. It is considered almost necessary for money to change hands in Vonatan in just about any interaction with the government or within the Council of Brothers.