The Defender and The Home:

Moral Authority beyond The State

My journey is the same as yours, the same as anyones. It’s taken me so many years, so many lifetimes, but at last I know where I’m going. Where I’ve always been going. Home, the long way round The Doctor.

By Unibot.

Introduction

During my time in NationStates, there has been at least one constant struggle in my political career the struggle to find a home. This title of this paper, The Defender and The Home, is personal to me as a player; I believe The Home is a central idea in the world of The Defender. Many defenders defend to protect others homes, they see The Home as something that should be respected from outsiders a sacred institution that should be loved, not invaded and annexed.

What is a Home? We often ask what a native is; we rarely ask what a home is a dictionary will tell you that it is somewhere that someone regularly lives, but this seems wrong to me. People live in houses, but they only call some of those houses, home. Home is where we feel we belong; its where animals instinctively know to return after the hunt. Theres an emotional connection between The Home and its residents they feel belongingness, safety, comfort. These are Maslovian psychological necessities which we desire out of need. Even on the Internet, belongingness, safety and such are still needs and they still motivate behavior, so I would argue that is not surprising at all that we seek out homes everywhere little regions and communities here and there, as the human condition dictates.

There are many reasons why over time we may have developed these normative ideas in regards to self-determination that is to say, why we may believe defending is the right thing to do. In Paradise Found, I mused that the ethics may be purely rationalist. Not invading others homes and helping others protect their homes, with this Hobbesian (or Rawlsian) method, promotes a fairer society one that helps protect our regions from a nightmarish, apocalyptic vision of NationStates where all (or most) of our regions are in constant fear of invasion and disruption.

Its also possible that it is much more basic than that; we may have this emotive response rooted in empathy, compassion and the instinctive negative valence of interpersonal harm. Greene et. al. has written a body of literature around the Dual Moral Process, which suggests philosophical differences in ethics may be a reflection of dissociable psychological patterns different ways of moral thinking: a slow, calculative (cost/benefit analysis) approach and a quick, primitive approach that relies on a very human response to direct forms of harm. This view would relegate Kantian theories and similar ideas presented in Paradise Found as mere ad hoc rationalizations of baser responses which may lack a coherent, rational idea behind them. But theres also something beautiful, something very human, about people just helping others because of something instinctive, be it empathy or kindness; we all want a home and we just naturally do not want to see others forced out of their homes and to seem them destroyed.

This paper is about The Defender and his Home if it were a Shakespearean tale, it would be a tragedy. The Tragic Joke of The Defender is that some of the people who go to the greatest lengths to protect other peoples homes in NationStates are the people who have the most difficult time finding a home in NationStates. The Home is an elusive concept for The Defender. He or she protects many homes everyday, but they often are not well accepted in their own regions these communities strain to accommodate them and their ilk they are quasi-tolerated idealists and nuisances, who are given just enough political rope to hang themselves on their own faith in the good of humanity and what they believe to be right.

The focus will be on The Defender in Neutral and Independent home regions which most regions are, at the time of writing. Neutral and Independent home regions present themselves as homes for players of all stripes, including Defenders. These regions will preach a vision of inclusion, which is false and collapses in upon itself and forces Defenders to choose between what they believe to be right and what the elites in their region believe is best for the region. Facing such a dilemma, the quixotic defender will paint him or her selves as unpatriotic and alienate themselves from the region for pursuing their beliefs. The Home, I will argue, challenges and does not tolerate alternative sources of moral authority, such as the individual beliefs of defenders.

To explain this broad picture of neutral and independent homes, I will have to delve into their conceptions of tolerance then I will have to discuss the moral theory of defenders versus independents, neutrals and invaders. From there I will establish that the defender, unlike independents, neutrals and invaders, holds a moral view that challenges the regional orthodoxy the weak tolerance of alternate moral views breaks under some political strain and the defender is subsequently alienated. There are many consequences for this phenomenon in general, defenders will lean cosmopolitan, while invaders encourage the regionalism of neutral and independent political societies. Meanwhile, this phenomenon can also explain why neutral or independent regions slowly progress towards invaderist and especially, anti-defenderists sentiments; the phenomenon may also provide converging theoretical interpretations of the downfall of defenderdom in the Post-Influence era, which I illuminated on in greater detail in Paradise Found.

Along the way, throughout this paper, generalizations will be made, generalizations that must be advanced. One generalization, for example, has already been assumed: that defenders often believe in a moral theory different than neutrals, independents and invaders. Surely, some defenders do not believe there is anything particularly unethical about invading, but these defenders are the minority and by and large have less of a problem finding a home within neutral or independent regions than the defender driven by moral belief this only provides further evidence for the overarching argument of this paper that the moral authority of defenderism places defenders in a difficult political position.

I will also argue that the relationship between defenderism and the state is like that of religion and the state in real life. Throughout this paper, there will be such comparisons made while I am an atheist myself, I believe that defenderism is a source of moral authority a values system, like a religion for NationStates and thus, what we are really witnessing is akin to the alienation of those who practice faiths that clash with the state and challenge its own political tenets. There have always been conflicts between church and state, while religious minorities are alienated, suppressed and regarded as unpatriotic. What we have not always understood is that these conflicts also occur in NationStates throughout its political and social history, without us recognizing it in the form of defenderism as a value system. The next section, in particular, makes such comparisons, given the history of tolerance in the church-state debate.

The False Promise of Tolerance

In neutral and independent regions, there is a promise of tolerance the narrative perpetuated by these political societies is that invaders and defenders are political equals in neutral and independent regions and to be respected equally under a common field of tolerance. This ought to mean, one would think, that in a neutral and independent region, a defender should be able to express his or her defenderist views freely and act as a defender, while also serving as a citizen in a neutral or independent region. But this is not the case neutral and independent regions structure their policies in such a way as to test the patriotism of defenders and pit their citizenship against their resolve to fight injustice abroad.

To understand how neutral and independent regions come to promote this narrative of tolerance, one needs a strong theoretical understanding of the idea of tolerance.

Rainer Forst distinguishes between different conceptions of toleration in real world political societies at least three of these conceptions are present in NationStates.

These three conceptions are easy to identify:

Permission tolerance is a classic model where a powerful majority permits a minority to express themselves an example of this would be a defender or invader region that allows minorities of either ideology to reside in their region although policies, biases and prominent discourses serve as a constant reminder of the overarching power relation between them and the social majority. Lazarus, at the time of writing, is such a region. Invaders are allowed as members, but they are a minority in a region where the social and political majority are defenders they are tolerated out of political expediency and a sense of fairness, but these minorities are not necessarily equal in standing.

Coexistence tolerance is a mixed model, where the relationship between the subjects is that of equals they pursue a system of tolerance out of mutual self-interest and a hope for social order and harmony. At any time, however, if the careful balance is ever broken and one side were to become more powerful than the other, the need for tolerance would vanish. This model mostly occurs in the cases of transitioning states, where invaderists and defenderists are desperately jockeying for power in a region but both are equal powers at times, British Isles, Osiris and The North Pacific among many other regions have flirted with this coexistence model.

Respect tolerance is the model, wherein subjects are equals and expected to respect others differences and regard their different ways of life as valid even if they see them as wrong. In the formal equality sense of respect tolerance, there is a public and private sphere the public sphere is supposed to pursue a fair society that justifies policies on a basis that can be universally accepted, while the private sphere is for people to pursue their cultures freely. This is the model that neutral and independent regions attempt to maintain in NationStates regions in the government, the public sphere ask that justifications for policies and decisions are not rooted in defenderism or invaderism, but instead something secular and universal to all: mutual interests. However, in the private sphere, defenders and invaders are allowed to continue to defend and invade freely. This public-private sphere distinction, and the call for mutual respect for differences, are the backbone of the tolerance regime in the political orthodoxy of NationStates and traditional neutral and independent regions.

There is, of course, an obvious connection between tolerance and religion as topics in the 17th Century, Europe was caught in a series of military conflicts as a consequence of the changing social and religious views which brought with it new challenges and power struggles. England was divided in the English Civil War, while Europe was caught in the Thirty Years’ War, which was incredibly destructive. The Age of Enlightenment, under scholars like Locke, Bayle, Voltaire and Spinoza, developed the idea of toleration a respect model, which separated the public from the private spheres (church from state), such that people of different faiths could come to live together in one country.

What remains to be seen, however, is whether this tolerance regime works in NationStates, specifically in regards to defenderism. In the next section, I will show how the system of tolerance falls apart when the public and private spheres collide in neutral and independent regions. The tolerance of the defender way of life, I will argue, is regularly threatened and challenged in neutral and independent regions for a variety of theoretical and practical reasons.

The Failures and Shortcomings of Tolerance

When does tolerance fail in neutral and independent home regions? Weve proposed it is in cases when ones public and private spheres collide this is to say that when someones life as a defender, conflicts with their life as a member of a neutral or independent home. In these dilemmas, they are forced to choose between their own moral beliefs or their region, which is why in a later section, we will characterize defenders as individualists they cannot put the security of one region before another, therefore the classical defender is lambasted as "unpatriotic" as not belonging as an “outsider” to the home that they desire.

Here are three scenarios where these spheres collide, where the defender is challenged in his or her beliefs.

“The Invading Region”

In this classic scenario, a home region decides to invade somewhere and its defender members must decide whether to side with their home region or not. A neutral/independent region may invade another region for many reasons: the target-region may be deemed spammers, enemies, Nazis, fascists or other undesirables. Alternatively, the neutral/independent may simply find an arbitrary invasion to be a wise use of resources as was the case with the controversial support that the North Pacific Army lent to the occupation of Warhammer 40000.

What role a defender plays in ones home region only magnifies the conflict of beliefs for example, as the leader of a region they are in the position to call for the veto of invading the region but on what grounds? Your beliefs of right and wrong?

As a soldier whose home region invades, he or she is also faced with the daily question of whether to stick with their beliefs that invading is wrong or agree to partake in their regions missions. What makes matters even more complicated is a soldier in their home region may be rationally deterred from being a defender a military may promote those who share the armys neutral or independent beliefs and distrust defender members, which systemically promotes an anti-defender hierarchy. Likewise, the simple focus on invasions may give defender-leaning members less opportunities to participate with their home regions army or demonstrate their merit and subsequently alienate them from the core group. Additionally, a member may simply just be deterred from joining their home regions army because they do not want to be associated with invader activities, or alternatively, they may be bureaucratically limited. Currently, for example, one must obtain special permission to serve in both the EPSA (The East Pacifics neutral/independent army) and a defender organization. These kinds of policies systemically lead defenders to either participate as a defender elsewhere or participate as a neutral/independent in their home region. These are tough, fundamental choices of whether to be a defender or to not be a defender, which the promise of tolerance suggests defenders should not have to face in neutral or independent societies.

In some senses, any army that invades is right to distrust defender members what is a defender to do if he or she finds details that could save an innocent region from destruction? Undermine his or her own regions activities or let the region be destroyed instead? Whether to defend against ones own region is a central question that many defenders are faced with answering when their own home region invades. A home region may ask of exceptionalism of its members, expecting defenders to not defend against their home region or face persecution for treason or another high crime.

These legal mechanisms do not serve a function of enforcing the law per se, so much as they promote the world views of the independent or neutral orthodoxy through punishment and shaming of those who deviate from the status quo.

“The Regionalists Expectations”

Regionalists have a deep-seated interest and fascination with the location of the WA member-nations of citizens in their home regions. For the classical Regionalist, there are always tests ways to prove ones commitment to the home region. This test, in the most radical of forms, requires that all citizens maintain their WA member-nations in their home-region to be granted the same rights and privileges as full, enfranchised members. Maintaining ones WA member-nation in one home region renders a player largely useless in undermining invasions and occupations, or otherwise the entire enterprise of defending other regions.

This is an extreme case, where regionalist policies expect defenders to renounce their defending activities abroad to participate in a region. This affects invaders too however, out of the two, only defenders would face an ethical dilemma with this policy. In most cases, however, regionalist policies are not this stringent, they may instead only require WA member-nations to be located in home-regions for higher, privileged positions, or the member-nation restriction may be exempted for on-duty members of the regions armed forces. Unfortunately, these policies and expectations still serve to challenge defenders ethically, given they have to choose between helping regions abroad or pursuing office and also, serving in the regions armed forces, as has already been established, may not be an option without renouncing their defender beliefs.

These policies not only serve to challenge defenders and pit them against their regions and their ethical code, but they also can act as social engineering: deterring members from becoming defenders through subtle, systemic and bureaucratic measures. In many regions, for example, voters are required to disclaimer is their current WA member-nation, or report to a central registry with a list of all their currently maintained switchers (puppet nations used for Military Gameplay). These small measures can go a long way towards making life difficult for defenders in their home region, since defenders need to constantly switch WA status between their puppet-nations. If say a defender votes on a bill on Monday and notes that their WA member-nation at the time is Bigtopia, it is likely they may have switched their WA member-nation hundreds of times (if it is a busy week) before Friday, when a vote closes. If the defender does not update this post before the votes closure depending on the region, this defender could be charged with deception and fraudulent claims (Bigtopia is no longer their WA member-nation) or the speaker may simply discard their vote, which has the effect of systemically suppressing an entire class of players opinions over time in the grand scheme of events.

You may wonder why this scenario is relevant to the topic of neutral and independent regions it is only relevant when neutral and independent regions consider regionalist measures. Some of these regions maintain and promote a cosmopolitan view.

“The Invaders Treaty”

In this scenario, an invader region pursues a treaty with a defenders home region the invader region promises non-aggression, in return for an alliance. The defender is conflicted, while in some senses, the treaty seems to offer much in the way of security for his home region. However, by passing the treaty, his home is associated, even allied with a region that is invaded, occupying and griefing many regions across NationStates is that something that his or her region should endorse?

This scenario personally occurred for me while I was Minister of Justice in The South Pacific. The New Inquisition sought an alliance with The South Pacific arguments presented by me to the Regional Assembly, surrounded around the idea that The New Inquisitions invasions of The Rejected Realms, Catholic, Belgium and many others would reflect badly on The South Pacific. Independents and neutrals were shocked a member would consider the safety of other regions abroad in rejecting a treaty with The New Inquisition.

Hileville, Delegate of The South Pacific, responded,

TSP has no diplomatic ties whatsoever to the regions of Catholic and Belgium so I really don’t care what they think of TSP being allied with TNI it has no bearing on our foreign policy.

Meanwhile Antariel, Minister of Foreign Affairs, using the rhetoric of tolerance, responded,

TSP needs to accept all nations, regardless of raider/defender. While I’m happy defenders like our region, I do not want them making it uncomfortable for raiders, which is what I think is happening.

The dilemma that defenders are faced with is whether to prioritize the safety and security of their own home region even to the detriment to others homes I believe this is the core dilemma faced in all of the scenarios. In the Invading Region case, the defender is expected to support his region and its actions abroad even when they threaten other regions, while in the Regionalists Expectations case, the regional measures request that defenders demonstrate their commitment to their home regions, even to the detriment of other regions (which are invaded and could use the support from defenders).

This core dilemma which underlies in all of the scenarios is a direct result of a fundamental feature of defenderism this fundamental feature has never be discussed in great depth before and it was quite a while till I as a defender personally discovered and understood this unsung principle of defenderism. I will call this principle, interregional equality. The principle of Interregional Equality largely is what makes defenderism irreconcilable with the realist underpinnings of neutral and independent thought in NationStates it is, thus, what causes these political dilemmas and the cracks that occur in our systems of tolerance, when we attempt to separate the public and private spheres of a defenders life.

Interregional Equality and its Implications

In the NationStates context: what exactly is Interregional Equality? Defenders believe that all regions (or most of them) have a right to self-determination to not be invaded. From this encompassing right, comes an understanding that all regions are equal in at least one respect: they all have a right to not be invaded and subjugated to a foreign force. In this understanding, largely any invasion is impermissible all regions deserve their sovereign right to govern themselves independently. This view of the interregional legal order from the defenderists perspective is idealistic: they see regions as moral equals, where the invasion of one region is equally as reprehensible as the invasion of another region.

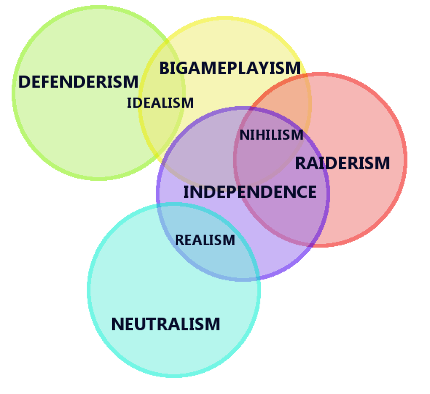

These ideas are fundamentally quite different than Independentism and Neutralism, which leads to the inherent tension between defenderism and the public realm as guided by independent or neutralist moral theory. This diagram visualizes the overlapping ideas shared by various schools of moral theory in NationStates:

In the diagram, I have suggested Bigameplayism and Defenderism share some ideas of idealism, because bigameplayers often share the defenderists view of interregional equality in regards to overt forms of griefing. Otherwise, however, the defenderist is largely isolated in political dialogue they do not share the inherent moral nihilism of independents, invaders and bigameplayers, who see nothing intrinsically wrong with invading. This may have been more obvious, since the opinion of independents, invaders and bigameplayers on the ethics of invading has been thoroughly discussed in other literature. However, defenderists also reject the realism of Independence and Neutralism. Why? Neutral and independent commentators share this realist belief that the guiding idea of a regions internal and foreign policy should be the unadulterated pursuit of the regions regional interests. In their classical approaches, defenderisms principle of interregional equality and this regionalist account of the selfish region are irreconcilable. Proponents of interregional equality would rather their home regions care, to some extent, about the invasion of non-allies across NationStates, the neutral and independent commentators however, would rather their home regions not even recognize the invasion of non-allies. If a region is not an ally, the neutral or independent commentator would see no justification from regional interests alone to care, acknowledge, observe or intervene in an invasion of these regions.

In the political setting of a neutral or independent home region, the defender simply possess ideas, such as the principle of interregional equality, which are not shared by neutrals, independents and invaders the defender is bound to be isolated and overwhelmed in debates and discussions. Their moral authority is beyond the state it lies beyond the regions obvious regional interests. The political discourse of regional interests and realism in the public realm, conflicts with the defenders private realm and their beliefs of what is fair, what is right and what is acceptable in NationStates. This makes the classic defender not only a political outcast and an outsider, but a regional pariah. Only the defender dares defy the orthodoxy that what is good is what is good for ones own region and what is bad is what is bad solely for ones own region. It is all too easy to paint these ideas that a defender holds as unpatriotic and perhaps, zealous.

Arguably, this is why so many defenders are cosmopolitans the regionalist ethos is hijacked by realism in neutral and independent regions, such that it is regionalist to put ones region before all other regions and reject the principle of interregional equality. Cosmopolitianism, however, weakly relates to the principle of interregional equality, at least in the sense of its rejection of such patriotic rhetoric. However, defenders may also pursue cosmopolitianism to achieve more intellectual freedom from the political orthodoxy of their neutral and independent home regions. Cosmopolitianism is uniquely individualist: it sees individuals as the main actors interregionally and promotes diversity of opinion. Alternatively, regionalism reifies the region and its core values and coerces members to adopt these values through policy measures or veiled threats of exclusion or ostracization. This helps to explain why many defenders are sharply regionalist in defender home regions (like 10000 Islands, Lazarus, Nasicournia, Texas), but they are sharply cosmopolitan in neutral or independent home regions the defenderist movements in many of these regions are led by self-described cosmopolitans, who promote diversity of thought and stand diametrically opposed to the regionalist narrative of "what makes a true citizen perpetuated by the centre of power in their respective home regions.

From the principle of interregional equality, I have shown how defenders alienate themselves and become outcasts in their neutral or independent home regions their beliefs lead them to becoming cosmopolitans and individualists in the face of alienation, political coercion and, in some cases, quite literally, persecution for their belief that the home ought not to be invaded any more than anyone elses region. From this core belief for defenders, follows a general unwillingness to let others homes suffer even if their own home region stands to gain from this misfortune. In the next section, I ask what conclusions then can we draw from this theoretical background and how The Defender and The Home as concepts can be united for once this is to say: how can defenders come to find the right home for them or build a more positive and accepting political setting for their views in their own home regions.

Concluding Thoughts

There is something quite romantic about the image of those who protect others, trawling the world in search of a home an outcast, an errant, a political messiah.

Defenders have some very powerful ideas of how their home should act, informed by their own moral beliefs, without them necessarily understanding that they even have these beliefs. The Defenders Home has a very unique relationship to everyone elses home: The Defenders Home is fair to all regions, in the sense that it sees itself equally valuable as other regions. Such a home region would not regard the invasion of other regions as nothing to be concerned about or not our business.

It follows from this that the defender will find home in a region that best promotes his or her value system the realism of putting ones region first to the detriment of others, alienates defenders from the regional discussion. In neutral and independent regions, defenders will pursue a very tolerant cosmopolitan order to make ideological space to practice their beliefs, but ultimately, the idealism of defenderism is best suited for regions that, are themselves, idealist in nature.

I have ended every one of my pieces discussing The Home; Polysemes ended by questioning what kind of home? The Transpacific Trade explained the path to home. A personal journey had begun. The title of Paradise Found was not an announcement of success, but a statement of intent.

Defenders travel from region to region; they go to where they are needed most. They go to where they feel they ought to go. I know now what we have always been fighting for every home we have or will have or have dreamt of having has made us who are today and what we believe.

We defend in the name of The Home. It is the heart, it is the cause and it will always be the destination.

Thank you for listening.

Yours truly,

Unibot.