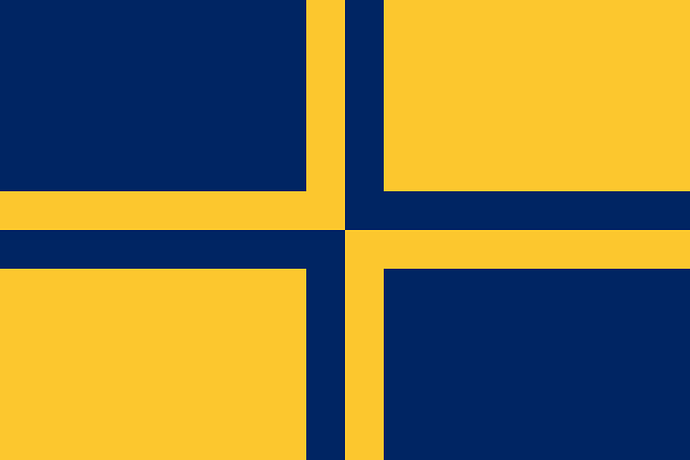

Flag: Quartered blue and yellow, divided by a counterchanged cross.

Nation Name (long): The Federal Republic of Venosta; La Republiche Federali di Venuest (S); La Republica Federala da Vnuost (V)

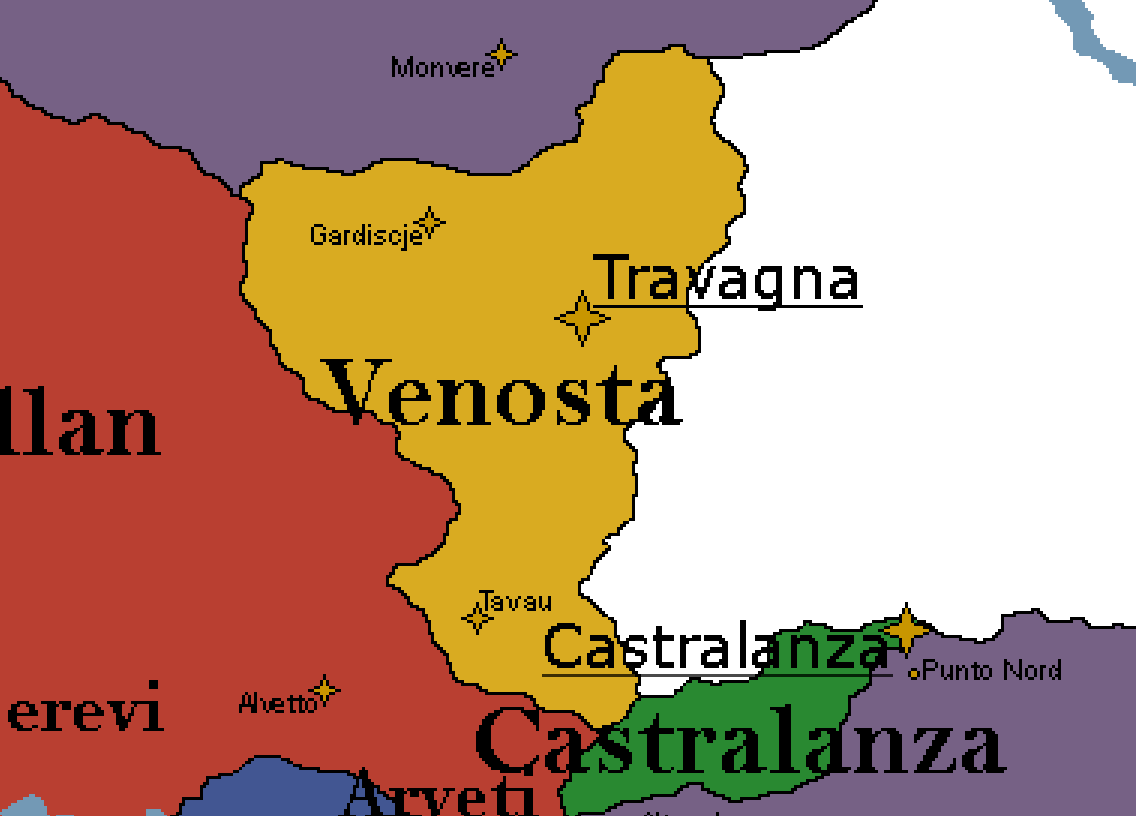

Nation Name (short): Venosta

Motto: “Simpri Unidis e Libar; Adina Unidas e Liber” (Always United and Free)

National Animal: The Aponivian Ibex (Capra ibex)

National Flower/Plant: The Stelutis Aponivis (Leontopodium nivale)

National Anthem: “Stelutis Aponivis” -Arturo Zardini

Capitol: Travagna [741,636]

Largest City: Travagna [741,636]

Demonym: Venostan

Language: Sagratan, Vargish

Species: Sagratan Human [46.4%], Vargish Lupine [48.3%], Other [5.3%]

Population: 16,844,924 [2021 Census]

Government type: Federal Parliamentary Republic

Leader(s): Presidenta Biatris Candreia - Chau di Parlament Alesh Cadruvi - Cjâf da Kongres Denêl Ermacora

Legislature: The Federal Legislature, consisting of the Vargish Parliament and the Sagratan Congress, acting as parallel [rather than upper or lower] houses, each representing a constituent state of the Federal Republic. The number of representatives are determined by the population of the constituent states; Congress has 161 seats, Parliament has 175 (one seat for every 50,000 people). The Cjâf and Chau are heads of government; the President is the head of state.

Formation: 1854 [Foundation of the Federal Republic; end of the Civil War], 1540 [Foundation of the Venostan Confederation; end of the Great Revolt]

Total GDP: $504,117,800,000

GDP per capita: $29,900

Currency: Valude/Valuta [pegged to the Aureo at a 4.000 rate]

Calling Code: +836

ISO 3166 code: VN, VEN

Internet TLD: .ven

Historical Summary: Starting roughly around 700 CE, Celanor began conquering the Aponivians, at that time inhabited by a collection of loosely-organized lupine tribes. The slow process of conversion to Lucerism began here, as ‘Sagrato’ eventually became a full province in 1092. Under Celanoran governance, Lucerism thrived and a small community of Celanorans established itself in Sagrato’s capital city, Tavate (now Tavau). A small minority of lupines continued to resist conversion, and pushed for greater autonomy over the next several hundred years. Coming under Volscine control in 1437, an influx of humans into Sagrato continued well into the 1500s. Criminals, adventurers, and nobility alike came to ‘Venosta’ seeking riches and power. The aforementioned lupine minority dissipated not long after as the last holdouts were converted. The native faith of the Vargish and their language were lost to time. Modern Vargish is a mix of Sagratan, Volscine Norvian, and said aboriginal language.

The Volscines proved fairly tolerant and granted a degree of autonomy not seen since before Celanoran rule. As a frontier march of the Volscine Empire, Venosta matured politically and culturally. Divided into several distinct regions, the constituents worked together to keep the Trans-Aponivian trade routes safe and bargained with the Volscines for more autonomy. Localized inter-regional conflicts erupted frequently over said trade routes but ultimately it was an era characterized by peaceful growth and unity. The War of Seven Emperors (1512-1537) upended this, and Sagrato threw in with the Cadrigano Pact in exchange for their independence after the war. Though the Cadrigano Pact succeeded, Sagrato was left in a weakened state afterwards. The Vargish capitalized on this right away and pushed for significant autonomy of their own. A coalition of Vargish nobility raised an army, marched on Tavate (later Tavau), sacked it, and wrested control of Venosta from the Sagratans.

This coalition rapidly grew to encompass almost every noble family and conte in Venosta, as none were influential enough on their own to contest the power of another. Thus, the Venostan Confederation was born; free from the Volscine yoke. Control over Venosta was completely decentralized and it was up to the individual states to administer themselves. Infighting was a given, and external threats thankfully few. Venostan mercenaries reached the height of their fame in 159X, distinguishing themselves in the Battle of X. Highly sought-after, these mercenary companies decided several key battles and only fell into decline after the disastrous Battle of X (164X). Though they continued to be a frequent sight on Novaran battlefields, the golden-age of the Venostan mercenaries had obviously come to an end by 1650. The next hundred years marked a period of gradual centralization and cultural blossoming in Venosta.

Following closely the leaps and bounds elsewhere in the world, Venosta paved the way for local innovation and the start of their own industrial revolution. In the area of steam engines and machine tools, Venosta proved an industry-leader. Though they missed out on the initial textile boom, they had caught up in most regards by the start of the 19th Century. A fortunate combination of idle-hands (labor surplus) and a wealth of natural resources made this possible, and Venosta’s economic surge continued exponentially. Practically overnight, it turned the country from a backwater to a modern and productive state in a very enviable position. The need for greater centralization became clear and over the next fifty years, Venosta struggled internally to achieve that. Sagratan leadership, in a general sense, disagreed with Vargish leadership on how to go about this. With local leaders tied up in a myriad of disputes, the task was mostly left in the hands of Venosta’s emerging industrialist class. Tensions ratcheted up in 1851 over resource rights in the regions of Bravuogn and Porsenù, where sizable coal deposits were discovered straddling the border of both constituencies. The government of Porsenù hired a company of mercenaries to take the land and secure it for the governor but were resisted by local lupines, armed with obsolete hunting rifles and farm tools. The Battle of Casparin’s Farm marked the start of hostilities between the two regions, escalating rapidly as Bravuogn raised a small army and marched on the town of Martigna, seizing the strategically-important ammunition factory in the outskirts of town. This pattern of retaliation attracted the attention of other regions, seeking to get a leg up over their adversaries. The conflict rapidly expanded and engulfed the whole nation, a daedalean web of alliances forming that jeopardized all that Venosta had become over the past century.

Despite this utter calamity, Bravuogn and several other regions remained standing at the end of it all. Reorganized into the Federal Republic under Bravuogn’s leadership, the new republic was initially very centralized. This aided in recovery, proving capable of putting the pieces back together and establishing law and order again. When the time came to initiate growth, government control loosened. The situation stabilized and Venosta came back from the brink. Venosta remained relatively peaceful and undisturbed until the Great War. Celanor’s policy of reconquest and their aggression towards smaller states like Solevera led the Venostan government to sign a secret defense treaty with Volscina, triggered less than a year later. For the entire duration of the Novaran theater, the Venostans adopted a strategy of defense-in-depth along the Aponivians, constructing several defensive lines and building up a large reserve force to plug holes and ensure that passes through the mountains didn’t fall. This was extremely costly; it required a Volscine expeditionary force of considerable size and a continuous stream of material aide through the Northern Aponivians. Said routes were constantly harassed by (reportedly) lupine saboteurs, which caused special (as in ‘species’) tensions to rise across the board. The result of this was a meat-grinder for the first year or two of fighting, before a general sense of pessimism and unwillingness to fight turned it into a series of low-intensity skirmishes. Even still, Venosta lost some 4.6% of its population (military and civilian deaths combined), a staggering figure considering Venosta only had some ten million inhabitants to begin with. The Great War scarred Venosta deeply, permanently embedded in their culture and guiding their foreign policy decisions for the next several decades. Following this, they adopted a policy of neutrality and refused to become involved in ‘foreign wars’.

The first noticeable change in course came in 1976, following the landslide victory of Laurinç Perabò in the general elections that year. A full sweep of both chambers by the Avanç/Vegnir coalition paved the way for the end of neutrality and an alignment of Venosta with Volscina. Entering the first phase of the Novaran Cold War, Venosta leased out land to Volscina to construct military bases and deploy ballistic missiles. Perabò proceeded to win three more elections, the longest winning-streak in Venostan presidential history. He retired before the 1992 elections, but Venosta stayed on course. His death in 1994 inspired a great deal of reflection on his legacy and to this day, public opinion is divided on the subject. Winning the 1992 election, Avanç/Vegnir lost the Vargish Parliament and proceeded to decline in popularity before fragmenting entirely in 1995. The time between Avanç/Vegnir’s collapse and the 1996 general elections saw widespread inaction on the part of the federal government, with many of Venosta’s largest parties embroiled in scandals and legal battles. Nevertheless, Fridolin Zala of the Parti Lavour Vargistisch (Vargish Labor Party) won the presidency by a slim plurality and was rendered a lame-duck by resistance from centre-right parties in Congress. In 2000, Zala won again but by a larger margin and was able to introduce a handful of budgetary reforms but nothing of note before the Volscine Civil War began. Sufficiently rattled and in need of a bailout, Celanora threw Venosta a lifeline in the form of the TATC (Tavau-Alenova Trade Compact), which in hindsight was more of a trojan horse than anything else. In time, the civil war ended and Volscina began clawing its way back to being a regional power, a process that was watched closely from Travagna. Ultimately, Venosta remains closely aligned with Celanora, wary of any further encroachment. The 2020 election brought the PLV back into the government for the first time in twenty years. President Candreia, leading the PLV minority government, balances pursuing her own agenda with keeping her party and the opposition in line. Chau Cadruvi, leader of the PLV’s democratic socialist wing, doesn’t lead parliament so much as challenge Candreia’s leadership and try to elevate his own standing in the party. Cjâf Ermacora on the other hand, leads the Gnûf Conservadôr (lit. ‘New Conservative’) party, a coalition of centre-right groups and organizations formed in 2020 immediately following the PLV’s election win. Together, the three vie for power and struggle to advance their competing agendas in the lead up to the 2024 general election.